Home | Articles | Search | Enroll | Equipment | Mello Chest | Souvies | Links | Updates

For all practical purposes, the evolution of the bugle temporarily ceased during the final years of the nineteenth century. It was during this time that brass instrumentation was becoming standardized. The focus of brass instrument manufacturers shifted to refining existing instrument designs instead of creating new instrument types. Since the military had provided manufacturers with explicit specifications for the bugles it needed, there seemed to be little need for experimentation. However, new markets were being created for the instrument that didn't exist prior to 1900. During this period, buglers outside the military realm began to implement changes to adapt the instrument to their activities.

Boy Scouts of America

As early as 1906, the Boy Scouts of America

incorporated the use of the "G" bugle for their troops. A merit badge also became available for proficiency on the instrument in

1917. Bugles for the Boy Scouts were produced by several firms including

Rexcraft, a brass instrument importer that was purchased by Buglecraft,

Inc. of New York.(64) C.G. Conn, Ltd. and H.N. White also manufactured

bugles that were endorsed by the Boy Scouts of America. Conn noted in

its 1930 catalog that its bugle is "noted for its easy blowing qualities

which make it an ideal bugle for the youngsters."(65)

merit badge also became available for proficiency on the instrument in

1917. Bugles for the Boy Scouts were produced by several firms including

Rexcraft, a brass instrument importer that was purchased by Buglecraft,

Inc. of New York.(64) C.G. Conn, Ltd. and H.N. White also manufactured

bugles that were endorsed by the Boy Scouts of America. Conn noted in

its 1930 catalog that its bugle is "noted for its easy blowing qualities

which make it an ideal bugle for the youngsters."(65)

Boy Scout drum and bugle corps began appearing after World War I (1914-1918). Most of these ensembles utilized surplus uniforms and instruments from the Great War.

Utilizing the same bugle calls as used by the American military, the typical Boy Scout Bugler could be expected to have a repertoire of no less than 17 calls. "Reveille," "First Call," "Tattoo," "Assembly," "Mess Call," "Swimming," and "Taps" would be performed dutifully by young buglers at Boy Scout outings and summer camps.(66)

|

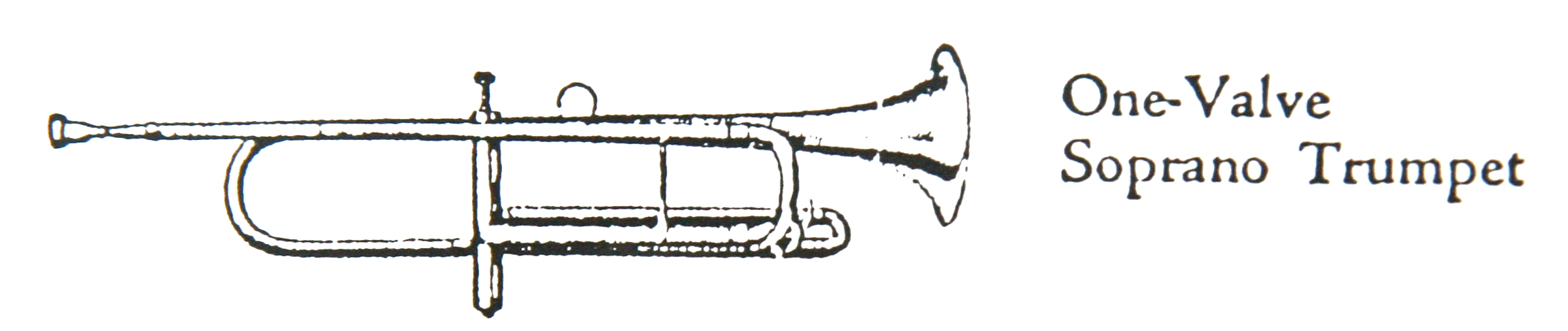

| The "Scout Trumpet" in "B-flat" featured in 1930s C.G. Conn, Ltd. catalogs featured a single vertical piston that dropped the instrument's pitch to the key of "F." |

As early as 1930, C.G. Conn, Ltd. featured a "B-flat" trumpet with one vertical piston valve. This instrument was called a "Scout Trumpet." Shaped like a "B-flat" trumpet, the Scout Trumpet's single piston dropped the horn's pitch four full steps.

The

bugling merit badge booklet printed in 1938 shows several scouts using

"G-D" piston bugles at the National Jamboree, which indicates modern

competition bugles were probably often used by scouts instead of the

"official" valveless "G" bugles.

The

bugling merit badge booklet printed in 1938 shows several scouts using

"G-D" piston bugles at the National Jamboree, which indicates modern

competition bugles were probably often used by scouts instead of the

"official" valveless "G" bugles.

|

|

| Tenite® bugle by Frank Aman. |

During World War II (1938-1945), strategic metals such as brass and aluminum were directed toward the war effort. As a result, synthetic bugles made with Eastman's patented Tenite® cellulosic plastic were adopted by the Boy Scouts.(67) These instruments were designed by Frank Aman (who incidentally created the "Tonette" plastic recorder used in elementary school general music classes for decades). The plastic bugles were replicas of standard military "G" field trumpets and were created specifically for the U.S. Army, but later adopted by the Marine Corps and Navy. Available in white and olive drab, these instruments were in use well into the 1950s.

Bugling would remain an inherent part of Scouting until interest began to dwindle in the 1970s. By 1986, interest waned sufficiently to prompt the Boy Scouts of America to discontinue its authorization of an "Official" Boy Scout Bugle.(68)

It's also important to note that Girl Scouts were equally adept at the art of bugling and utilized the instrument in a very similar manner as their male counterparts.

American Legion

American military forces in Europe during World War I (1914-1918) were greatly impressed by British and French drum and bugle corps. Inspired by the European corps, the American Legion was formed in 1919 for war veterans and shortly thereafter began forming drum and bugle corps in the United States. The Legion selected the "G" trumpet for these ensembles because it was standard for army foot troops at the time.

|

|

| Conn's American Legion Bugle was available in low- and high-pitch "B-flat" and "G" (models 10-L through 13-L, respectively). |

The number of active drum corps formed by the American Legion increased dramatically during the 1920 and 1930s. As the amount of corps increased in number, so did the competitions. Soon, bugle designs known as "American Legion" were utilized by some competing corps. These instruments are easily identifiable by their length and represent a design trait that would remain consistent in drum corps brass instrumentation through the late 1960s. Drum corps competitions also sparked creativity in the design of bugles in tenor and bass voices. These were valveless bugles that had moveable slides for tuning purposes.

"Two Pitch" Music in the United States

The use of tuning crooks for bugles was documented well before the twentieth century, but their use in the United States at the turn of the twentieth century prompted new melodic options for the burgeoning drum and bugle corps activity.

War Department documents chronicle the practice of utilizing "two pitch" music for bugles. While one would assume the term actually indicates music utilizing two bugles of two "pitches" or keys. Ensembles with bugles in the key of "G" and "D" were somewhat commonplace prior to 1920. The military did not make it a practice of providing tuning crooks for its buglers, but seemed not to dissuade ensembles from producing them on their own. Suggestions for the use of these tuning crooks were explicitly provided in governmental text:

In playing this class of music, known as "two-pitch" music, the corps is divided as evenly as possible, half of the buglers attaching the D crooks to their instruments, and the remainder continuing to use theirs in they key of G, and resting while the other half plays. This two-pitch music is a pleasing diversion, but should not be so constantly used to become tiresome or monotonous. Special work is required to train the buglers to commence the various strains confidently, and to rest at the proper time.(69)

Military drum and bugle corps prior to 1920 often utilized a bugle section divided into four sections. The first three sections consisted of players utilizing "G" bugles. Bass bugles pitched an octave below these instruments could also be utilized. These ensembles would perform ceremonial "flourishes" on their own or play strains of military marches with the regimental band. One example of these flourishes would be the introduction utilized with "Hail to the Chief" used to introduce the President of the United States at ceremonial functions.

|

| Flourishes were commonly performed by buglers who performed along with regimental bands. Reprinted from http://www.music.vt.edu |

As the two-pitch music began to be used regularly by corps, specialty bugles were manufactured in the key of "D" to compliment the "G" bugles. The extent to which these "D" instruments were manufactured is unknown, but specimens are currently very difficult to locate.

Bugles pitched in the key of "G" appear to dominate this era, but it's important to note that two-pitch music was also performed with instruments in "B-flat" and "F."

Introduction of the "G-D" Piston Valve Loop

During the 1920s, a bugle with a single vertical piston (based on the Bersag horn used in Italy since the 1870s) was devised and voiced in soprano, tenor and bass and sold in North America. The single piston featured on this instrument was incorporated into a loop of tubing that lowered the pitch from "G" to "D" (hence the term "G-D" bugle).

|

|

|

Three voices of single horizontal piston bugles in the key of "G" offered by Fred Gretsch Company in their 1936 catalog. |

Several people have been credited with introducing the piston bugle to the United States. Allegedly, Arthur "Scotty" Chappell "rediscovered" the "D" crook for the "G" bugle that led to the adoption of the piston valve for the bugle. William F. Ludwig purportedly encountered Chappell's "unique" instrument and replicated the concept with a rotor (eventually replacing the rotor with a piston) in order to sell it to drum corps with his percussion instruments.(70)

|

|

An elegantly designed Conn 86L "G-D" single piston bugle from the 1930s. Reprinted from the Conn Loyalist. |

|

William F. Ludwig, Jr. believes his father first encountered the "D" piston concept while he traveled abroad in 1927 as part of the American Expeditionary Force's ten year reunion in Europe. Ostensibly after the celebration in Paris, Ludwig visited Italy and allegedly witnessed a Bersaglieri horn in use.(71)

|

|

| William F. Ludwig (r) and his son (l). Ludwig senior was a percussion pioneer who also had an important role to play in the evolution of the competition bugle. |

Despite the ingenuity of drum corps' early pioneers in the United States, their adoption of the "G-D" bugle was anything but original. A version of the Bersag horn (featuring a single piston dropping the instrument's pitch from "B-flat" to "F") was available for purchase in the U.S. as early as 1888.(72) However, the placement of the piston in the horizontal (versus the vertical position) does appear to be uniquely American.

There's evidence that sometime during, or shortly after 1927, William F. Ludwig contracted the William Frank Company of Chicago to fabricate an instrument with the piston positioned horizontally instead of vertically. The purpose of the alteration was to conceal the piston from American Legion drum corps judges because of the Legion's ban on all bugles accept for valveless militarily "G" bugles.(73) Catalogs from this period also cite the aesthetic effect of cloaking the piston by allowing performers to play them in the traditional one-handed manner.

It's important to note that the "G-D" bugles were actually duplex instruments. The intent of the piston valve was to change the instrument's key, not to enable the bugle to facilitate a diatonic scale or melodic pitch changes. The desire was to provide one instrument that could perform two-pitch music.

|

| Valve lock used on early "G-D" bugles to prevent the usage of the valve during competitions. From the Leedy Roll-off No. 4, 1937. From the collection of Jack T. Carter. |

As corps began to exploit the usefulness of the piston, the American Legion National Contests Committee body decided to "even the playing field" for corps not utilizing the piston bugle. In order to protect the majority of corps still utilizing valveless instruments, the American Legion required each piston bugle used in competition be equipped with a "lock" that in essence "sealed" the piston in order to prevent it from being opened or closed at the player's will during performances. Each corps would have to choose pistons on their horns to be locked in the open or closed position, offering the corps the option of utilizing instruments in the keys of "G" and/or "D." This configuration would allow performers to access more notes, but it also effectively limited the amount of instruments that could play all their pitches in unison.(74)

|

|

|

Competition among bugle manufacturers was fierce during the 1930s. In addition to offering helpful manuals to drum corps organizers, firms also elicited endorsements and used contests to promote their instruments. Holton recognized state bugle champions in an advertisement campaign in 1934. |

Music books and manuals were made available to corps by instrument manufacturers and distributors. Some of these manuals provided the corps' organizer detailed information that could be used to fund, rehearse, and perform their corps. For example, the Ludwig & Ludwig Drum Corps Guide published in 1932 offered information on contest etiquette, use of drum corps at funerals, drill maneuvers used by successful corps, tips for a successful convention, and "stunt night." Once uniforms and equipment were procured, it wasn't unusual for a newly-formed drum corps to begin performances within mere weeks after initial rehearsals.

|

||

| A U.S. Marine in dress blues featured with his bugle (with tabard) at the carry position. From Manual for Field Musics, 1935. |

Suggestions offered to buglers by written manuals and instructors were straight forward:

Blow into the instrument with an attack as if saying the syllables "too" or "ta" with considerable force. After starting the tone, hold it out strongly and steadily without waver as long as possible with comfort...Be sure the mouthpiece is in the middle of the lips and that no less than one third of the mouthpiece is on either lip. The attack or start of the tone should be sharp, snappy and decisive.(75)

The U.S. Marine Corps adopted the "G" piston bugle in 1938 "to increase the musical scope of the drum and bugle corps." Claiming that these modern bugles "have truly given a new life, a new character, and a new brilliance to the drum and bugle corps," a manual published by the U.S. Marine Corps set forth the proper protocol that was to be utilized by its military corps. Manual for Field Musics was published in 1935 and offered a unique glimpse into the type of musical training that a military bugler could expect. Directions for the care of the bugle with explicit instructions to beginners were included, along with other inexplicable information such as the following excerpt:

Two hours of patient intelligent practice will help more to acquire proficiency than 10 hours of promiscuous blowing...Never play within an hour after meals. This give the gastric juices a chance to perform their digestive function and thus does not rob the lips of the needed saliva required for proper vibration.

|

|

|

Ludwig & Ludwig offered a family of B-Flat-F piston bugles in 1932 that were adopted by the U.S. Marine Corps and several competitive drum corps. The catalog's narrative identified the incompatibility between these instruments and their line of G-D bugles. |

The Marine Corps also utilized a piston bugle pitched in the key of "B-flat." Like the "G" instruments used by competing drum corps, the "B-flat" instruments were offered in soprano, tenor, and bass voices. The "B-flat" instruments were desirable by the military (and many public corps) because of the ease with which they could perform with marching bands with "B-flat" trumpets and clarinets. In a similar fashion of the trumpet and drum corps of the late 1800s, these "B-flat" corps would play alternately or even with the band while on the move. "B-flat" bugles were also paired with fifes and drums. The trend of using "B-flat" piston bugles in the United States, however, was short-lived.

|

|

| C.G. Conn's cleverly designed "Three-in-One" (model 26-L) trumpet available 1928-1930 included an optional slide that allowed the horn to be placed in keys of G, F, and B-flat. The instrument was nearly 30" long and featured a compact 4-5/8" bell diameter. |

| The West Point Hellcats utilize B-flat/F single piston bugles (link). |

Introduction of the Baritone Bugle and French Horn Bugle

The bass bugle used by corps just prior to 1920 eventually evolved into what was to become known as the baritone bugle in the early 1930s. Ludwig called them "Baro-tone" bugles. During the 1930s, the typical bugle choir consisted of the soprano, tenor, and baritone voices. Sometimes they were referred to the "first," "second," and "third" voices.

|

|

| C.G. Conn, Ltd. offered a bass bugle (model 22-L) in B-flat in its 1930 catalog. This instrument was 27" long and featured a 6" diameter flare. |

As the baritone bugle was introduced to drum corps, drum corps manuals of the time suggested that a proportion of one baritone per four soprano bugles be used. It was suggested that performers selected for the baritone should not be "timid."(76) It was anticipated that this instrument would produce the same amount of volume as three soprano bugles.

|

|

|

Holton offered a G-D baritone bugle, as well as a B-flat-F version in its 1940 catalog. |

|

The baritone bugle was initially designed to have a "trumpet" tone, instead of mimicking its low brass namesake of the concert band. These instruments were created to blend well with the "G" sopranos. The fundamental performance technique utilized by early baritone buglers was identical to soprano players.

|

The French horn bugle (pitched an octave lower than it is played) was allegedly conceived and manufactured by Whaley Royce in 1941, according to literature published by Whaley Royce in the 1960s. French horn bugles quickly gained favor because of their ability to sound more notes than other bugles.

|

|

The Conn 92L French Horn "G-D" Bugle used during the 1950s (from the collection of Kenny Norman reprinted from the Conn Loyalist). |

Slip-Slide Techniques of the Re-introduction of the Rotor

Beginning sometime in the mid to late 1950s, performers began to practice of polishing the tuning slides on their bugles and manipulating them like trombone slides in order to change the pitch of the bugle. The result was a clever method that lowered the bugle's pitch by a half or full step, thus enabling the bugle access to many notes never before available on these instruments. Drum corps performance pioneers such as French horn bugle soloist Pepe Nataro and baritone bugle soloist John Simpson exploited "slip-slide" techniques before stunned audiences during the 1950s. This practice must have seemed innocent enough to performers and spectators, but this curious performance technique would set in motion the desire for the chromatic bugle and forever change the drum corps activity.

Despite the success, the "slip-slide" technique was difficult to master for most players and did not easily facilitate quick pitch changes. Around 1957, new bugles were made available with the option of a factory-installed secondary "slip-slide" or rotor valve. The Legion eventually authorized the use of a rotor valve in response to the "slip-slide" phenomenon and to permit musicians to accomplish the same effect more efficiently.

Secondary rotor valves were also devised for "G" bugles that lowered the instrument's tone by a half-step, full-step, or even a step-and-a-half. It's unclear which manufacturer actually introduced the secondary rotor valve. Since experimentation among corps during this time period was rampant, it's likely that this introduction occurred simultaneously among numerous manufacturers and amateur designers.

|

Photographic evidence from the period suggests many corps opted to utilize bugles with only a primary piston during the early 1960s. Despite the fact that many corps utilized "slip-slides" as a secondary "valve" for their bugles, most corps utilizing an additional valve were choosing rotor assemblies for their instruments by the mid-1960s. These rotors were cleverly designed into the removable tuning slides and were actuated by the left thumb or forefinger. Due to the design characteristic, drum corps could purchase replacement tuning slides with integrated rotor valve assemblies to easily upgrade their current instruments. This allowed corps to remain competitive at minimal cost.

Through the 1960s, there was a great diversity among the configurations utilized by corps. Until the next major rule change in 1968, bugles were available in North America with a dizzying variety of options. "G-D" bugles were available with a piston only, with a piston and "slip-slide," or with a piston and an "F#" rotor, an "F" full-step rotor, or even a step-and-a-half "F-flat" rotor!(77) Since each type of secondary valve required a different fingering system for the instrument, one can only imagine the amount of confusion experienced by novice brass players attending their first drum corps rehearsal!

Rotors would remain an integral component of the competition bugle until it was phased out in 1976. Traditionally, the rotor valve has many advantages over the piston valve such as increased durability and dependability. The rotor is a closed system that is much less vulnerable to the dust and airborne debris associated with outdoor performances and rehearsals. However, the rotors developed for the drum corps activity were generally of poorer quality and required painstaking maintenance.(78) Had a higher quality rotor been devised for corps, it seems likely the piston valve could have been supplanted by the rotor and could have remained the preference for manufacturers.

Introduction of the Contrabass, Mellophone, and Euphonium Bugles

|

|

| Reilly Raiders introduce a contrabass bugle (left) in their program in 1962, as featured in this photo from the September 12, 1962 issue of Drum Corps News. |

|

It is generally believed that the contrabass bugle was first fabricated in 1959 by Whaley Royce Company, Ltd. of Toronto. However, it has also been suggested that Getzen salesman Sandy Sandberg invented the contrabass bugle.(78a) This double "G" contrabass was pitched an octave below the bass baritone bugle and was made exclusively for the Geneva Appleknockers. According to the 1967 Whaley Royce instrument catalog, the contrabass bugles was "on the market before drum corps were ready for it." However, the instrument was "re-introduced" five years later and enthusiastically accepted.(79) Some Canadian corps briefly experimented with a contrabass bugle in the key of "C."

The introduction of the contrabass was not without controversy. Resistance from the drum corps "purist" and the American Legion threatened the future of the new horn. Correctly sensing the activity would be harmed by the movement to "black ball" the contrabass, Don Angelica, Musical Director for the Garfield Cadets and the Hawthorne Caballeros offered a compelling and successful plea to readers in the December 8, 1962 issue of Drum Corps News (excerpted here):

To those critics who feel that this is a step away from drum corps instrumentation I say let us lock up the slides, let us get rid of the French horn and the bass bugle and let us return to the music played 25 years ago. This is certainly not an effort to make a band of the drum and bugle corps, it is an effort to further the musical values of the bugle line, it is an effort to raise the quality of musical arrangements, it is an effort to solve the problem of poor intonation in the low register, and most important an effort which will I am sure, provide a more musical drum corps show.

To those who say it is an awkward looking instrument let me state that I have seen some people make a soprano horn look awkward, and I am quite sure those who have seen Garfield and Hawthorne with the contra will not accuse them of looking awkward, if anything it adds a new effectiveness to the visual picture of the show. It is in my opinion, if handled properly, an aristocratic instrument which is not only a musical asset but also a visual one.

|

|

|

Although Dominic Delra is credited for the design of the first mellophone bugles that he contracted Whaley Royce to fabricate, the Toronto Optimist (the corps nearest the Whaley Royce facility) received credit in the April 8, 1964 issue of Drum Corps News for introducing the mellophone to drum corps. Photo reprinted from NanciD's drum corps blog. |

In 1957, the C.G. Conn Company created the first mass marketed bell-front mellophones in North America. Called the mellophonium, the instrument maintained the characteristic round shape of the mellophone and was somewhat similar to the custom-made bell front instruments built by the C.G. Conn Company for jazz artist Don Elliott a few years prior. The Stan Kenton Orchestra also prominently featured a four-man section utilizing stock Conn mellophoniums between October, 1960 and December, 1963. Due to the success of the mellophonium in marching bands, it was inevitable that the concept would be utilized by drum and bugle corps.(80)

Whaley Royce Company's "Imperial Mellophone" was first developed and designed by Dominic Delra, the music director of the Interstatesmen of Pittsfield, Massachusetts. Delra created a prototype and had the Whaley Royce Company fabricate copies in the fall of 1963. The Interstatesmen purchased six mellophone bugles and used them for the first time in Canada in Quebec City in February 1964.(81) However, photo evidence from Drum Corps News appears to show mellophone bugles being incorporated into an exhibition performance by the Interstatesmen in 1963. The three mellophone buglers in the photo have been identified as Joe Benoit, Ray Benoit, and Al Richards(81a). By the summer of 1964, the Whaley Royce mellophones were being added to the French horn sections of the Springfield Marksmen (see below) and the Belleville Black Knights.

|

|

The Interstatesmen drum and bugle corps in 1963 were the first corps to utilize production model Whaley Royce manufactured mellophone bugles. The highlighted portion of the photo above shows three mellophone bugles and three French horn buglers. The Toronto Optimist field tested prototypes by Whaley Royce prior to units being fabricated for Delra. Photo from Drum Corps News. |

|

|

| Part of the Springfield Marksmen's inaugural mellophone section performing with their new Whaley-Royce mellophone bugles on July 11, 1964 as featured in Drum Corps News. Photo reprinted from NanciD's drum corps blog. |

At about the same time a production mellophone bugle was being distributed, the euphonium bugle was also being created at Whaley Royce in Toronto. Pitched in the same octave as the bass baritone, the euphonium was a much larger and imposing instrument. The euphonium's intended purpose was to add a darker tone quality to the bugle choir's low brass section. Some corps were pleased enough with the instrument to replace their entire baritone section with them--much to the horror of the performers designated to perform with these "widow makers."

|

| A Whaley Royce euphonium from the company's 1967 catalog being held by a member of the Toronto Optimist. The Canadian manufacturer is believed to be the firm to first offer a production euphonium bugle. |

By the mid-1960s, the bugle choir had grown to encompass three octaves with four voices of instrumentation.

Click here for part four

Endnotes

(65) C.G. Conn, Ltd, General Price List E (14 May 1930) 15.

(66) Boy Scouts of America, Music and Bugling, (North Brunswick, New Jersey, 1968) 41.

(67) Brett A. Mills, National Scouting Museum, Letter to Author, 16 Jan 1996.

(68) Ibid

(69) W.T. Duganne, The Army Bugler, W.D. No. 1019, (Washington, D.C.: War Department, Government Printing Office, 1920) 35.

(70) Jodeen Popp, Competitive Drum Corps: There and Then to Here and Now, (Des Plaines, IL: Olympic Printing Company, 1979) 24.

(71) William F. Ludwig, Jr., letter to author, 05 Dec 1995.

(72) C. Bruno & Sons, Illustrated Catalogue, (New York, 1888) 56.

(73) William F. Ludwig, Jr., letter to author, 05 Dec 1995.

(74) Nick Michielli, Letter to the Editor, Drum Corps News, 15 Jan 1976.

(75) Ludwig & Ludwig, The Ludwig & Ludwig Drum Corps Guide, (Elkhart, Indiana: L&L International., 1932) 13.

(76) Ludwig & Ludwig 13.

(77) Whaley Royce Co., Ltd, Drum and Bugle Corps Accessories Catalog, January, 1967.

(78) Zigmant Kanstul, letter to author, 20 Mar 1996.

(78a) Ibid

(79) Whaley Royce Co., Ltd, Drum and Bugle Corps Accessories Catalog, January, 1967.

(80) Scooter Pirtle, "The Stan Kenton Mellophoniums," The Middle Horn Leader, May, 1994.

(81) Whaley Royce Co., Ltd, Drum and Bugle Corps Accessories Catalog, January 1967.

(81a) Al Richards, Sykliners Open Forum posting, April 27, 2007.

Home | Articles | Search | Enroll | Equipment | Staff | Souvies | Links | Updates